Biochar Production System

| 2017-18 University of Idaho Capstone Senior Project | |

|---|---|

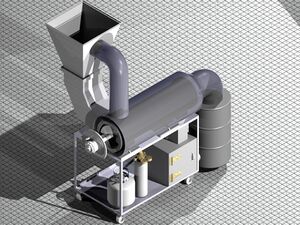

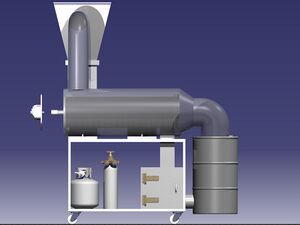

| Final Design Render | |

| Sponsors | Industrial Assessment Center (IAC) funded by U.S. Department of Energy; University of Idaho, College of Engineering |

| Team Name | Biochar |

| Duration | Fall 2017 - Spring 2018 |

| Company Liason | None; N/A |

| Faculty Advisor | Dr. Dev Shrestha |

| Team Members | Jake Hall, Adam O'Keefe, Rachel Rosasco, Will Seegmiller, Joe Stanley |

| Questions or Comments? | engr-biochar@uidaho.edu |

| Purpose Videos | One-Minute Overview |

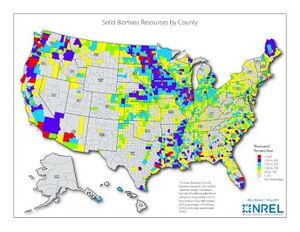

In the 150 miles that surround the area of the Palouse nearly 2 million tons of waste biomass are accumulated each year. This waste is nearly valueless, taking up valuable space at lumber mills that could be used instead for equipment or inventory. Currently lumber mills try to sell this waste biomass at up to 25 dollars a ton, and in many cases are even having to pay someone to ship it away. The idea is to take this low value waste and turn it into a high value product, biochar, which can be sold for $2000/ton. Along with the problem that the lumber mills are having, the farming industry is struggling with topsoil degradation. Currently the topsoil is becoming less and less nutritious which is creating problems for an industry trying to feed a growing population. As a consequence farmers are needing to use more fertilizer to grow the same number of crops. This causes both economic and environmental problems, as this is a cost intensive solution and reduces the amount of phosphorus available, a key ingredient in fertilizer. All these problems create a business environment with a unique opportunity to allow our product to kick start a brand-new market here in the U.S.

Development on this, the original prototype, has ceased. However, a "beta" version of the project is currently being developed by some of the original students. For more information, view the "Beta Version" here.

Development and Project Goals[edit | edit source]

Our team’s mission is to develop and prototype a model of a scalable, practical retrofit for modern, industrial boilers that will produce biochar for sale and heat energy. This design must account for multiple variables and allow control of input and output flow rates amongst other factors.

In an attempt to take advantage of biochar’s potential and start a new market in the U.S. the team is designing an attachment that will go on a pre-existing boiler and produce biochar at a continuous rate. This system uses exhaust heat from the boiler system to pyrolysize the waste biomass to produce biochar. This means that it will not take any resources the lumber mill already has. It is recycling various aspects of their operation to provide an economically viable solution to the biomass waste that is accumulation. This device will move lumber mills towards a minimal waste operation.

To summarize, our goals are:

- Design a biochar reactor.

- The reactor should function as an accessory for existing boilers and furnaces.

- The reactor should use as little energy as possible.

- The reactor should be easy to retrofit and as non-invasive as possible.

- The reactor should produce biochar at a continuous rate, not through a batch process.

- Build a prototype.

- The prototype should be portable.

- The prototype should be fully functional.

Design Specifications[edit | edit source]

The needs and constraints designated by the client for the final design include: continuous process, easily integrated to a boiler system, scalable industrial design, energy efficient design, dynamic control system, and function as heat exchanger.

This design should be unique and different from other available biochar reactors in the sense that it should operate using available heated gasses exhausted from a preexisting boiler system. In a sense, this system should serve as an attachment that can be added to existing boilers so that they are able to incur additional value from waste biomass.

Mechanical Specifications[edit | edit source]

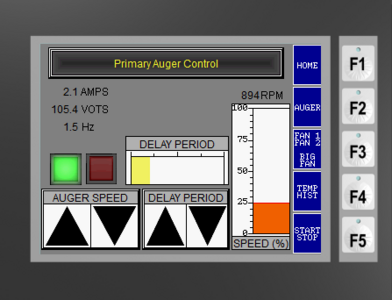

Our team has decided to work with incorporating a 1/2 Horsepower 3-Phase motor rated for 3600RPM as the primary auger energy source. To allow for ample cook times for the biochar, the motor will be geared down with a system of pulleys and belts. The gear reduction ratio is just over 1000:1. Not only will this supply the necessary speed reduction, but it also greatly increases the amount of torque delivered to the auger system, allowing for effective transportation of the biomass through the reactor. This motor and gearing is combined with the use of brass-bushings that support the auger shaft. Bushings were selected due to the fact that high-temperature-rated bearings are not only expensive, but potentially quite difficult to utilize.

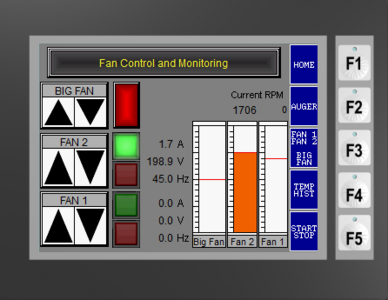

In addition to the drive motor, the design makes use of three existing fan and motor assemblies. Two of the fans are small 230V squirrel-cage fans, and the third is a much larger 120V 1/2 Horsepower squirrel-cage fan. The three motors are to be speed controlled by use of the control systems described below.

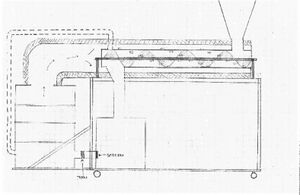

The design makes use of a built-in "boiler" which, quite simply, is a 55-gallon metal barrel with a large 55kBTU rated propane burner mounted in the bottom. The boiler requires a large hole in the top for heated gasses to escape and enter the auger-based reactor.

The auger-based reactor system uses an inner and outer chamber system; the inner chamber contains the auger and the biochar which is being cooked, while the outer chamber contains the heated gasses exhausted from the "boiler". The inner chamber has many appendages not unlike heat-sinks built onto its exterior. This creates additional air-turbulence inside the outer chamber, and thus allows for greater heat transfer to the inner chamber, and by extension, the biomass. The inner chamber is made of a stainless-steel sheet rolled into a tube with many 1-inch "heat sinks" of 1-inch angle-iron welded onto its outer surface.

The biochar-collection bin is specified to be created from an old 2-drawer filing cabinet. A large hole cut in the top of the bin allows for cooked biochar to enter the bin, and the existing drawer is used to contain it and collect the material for easy extraction. The drawer and cabinet is intended to be sealed by use of furnace-type gasket material and heated gasses are to be extracted from the bin by use of one of the blower-fans previously described.

Electrical Specifications[edit | edit source]

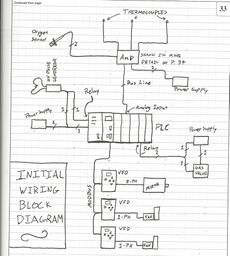

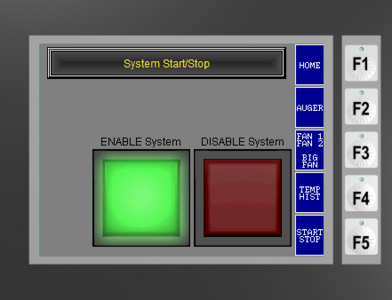

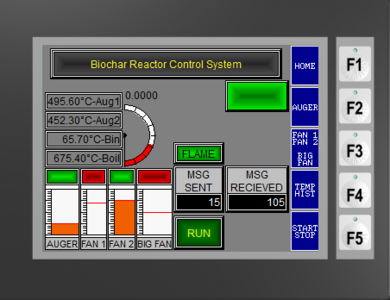

Project designs were requested to use an existing Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) produced by AutomationDirect; the Productivity2000. The PLC was a modular system with room for a power supply, main controller and communication board, and 4 I/O modules.

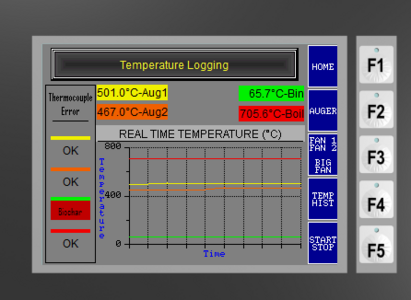

The PLC makes use of 4 modules; a toggle-switch based digital input, a relay-based digital output, an analog input reading voltage, and a Thermocouple input module. In addition to the modular I/O, a touchscreen control panel is used for user interface and will control motor operation and display temperature and oxygen levels. The PLC is also responsible for basic operations including the system-startup procedure, and it operates in one of two modes, Demo-Mode or Active-Mode. The Demo-Mode only allows operation of the motors and does not use the startup procedure to ignite the fuel supply, the active mode allows control of the fuels supply and automatically engages the startup procedure.

The project requires the control of 3 motors by use of GS1 Variable Frequency Drives (VFD's) also produced by AutomationDirect. These VFD's use industry standard Modbus protocol over a 2-wire RS-485 connection as their primary control communication. This connection supports addressable operations, thus allowing all three VFD's to communicate over the same connection.

In addition to the three VFD-controlled motors, it is also necessary to control an additional 1/2 horsepower single-phase motor whose rated current draw far exceeds the ratings for the VFDs used for the other motor controls. This motor still requires speed control, however, and thus a system of Pulse-Width-Modulation (PWM) is used to control the motor. A electro-mechanical system using relays operating on a 1-second fixed period controlled by the PLC is used to control and energize the motor. This system will work due to the motor's enormous natural turn-on or turn-off time. It takes the specified motor 20 seconds or longer to turn on and rev to full speed, and it takes even longer to turn off and stop. This means that a PWM system with a 1-second period works effectively for the system.

The electrical system is also specified to ignite the fuel supply of propane. To do this, the PLC uses one of the relay contacts to energize a single-phase 120-3000V transformer designed for neon-signs to create an arc and ignite the propane burner. The PLC uses another relay contact to energize a normally closed solenoid valve and open the propane line to allow fuel to reach the burner. This process is monitored by the temperature probes and the PLC so that if the temperature does not rise (the fuel doesn't ignite) the system goes into a lockout-state where it shuts off the fuel supply and vents dangerous gasses.

This project also makes use of safety precautions such as emergency stop buttons. These are connected directly to a electro-mechanical lockout-relay that, if activated, removes all power from the entire system which will force valves closed and all systems to stop.

Thermal Specifications[edit | edit source]

From speaking with our graduate student advisor, Brian Hanson, and various sources online who describe the production of biochar and the requirements of an effective system, our team came to understand the thermal requirements. Temperature is a major component of the resulting material output of a pyrolysis system. Cooked under higher temperatures, biomass tends to release higher amounts of volatile gas and tar-like bio-oils. Alternatively, when cooked under lower temperatures (those around 450°C), pyrolysis tends to lend a higher biochar yield, and a smaller amount of gas and oil.

Due to this understanding of the thermal constraints, our team has conducted testing to determine the quality of biochar cooked in the range of 450°C.

Project Learning[edit | edit source]

Biochar dates back 2,000 years to a civilization in a remote region of the Amazon Basin where regions of dark, highly fertile soil has been discovered. It is theorized that the ancient Amazonians used a process known as “slash and char”, where the biomass (plant material) were cut, ignited and buried to smolder. This process allowed the Amazonians to support a diverse agriculture and explains how their population grew to immense numbers.

Biochar is rich in fixed carbon and has an enhanced surface area caused by micro and macro pores that easily absorbed and maintain moisture and nutrients. When it is integrated into soil it works to bring soils from both ends of the spectrum, sandy and clay soils, to a more nutrient rich middle.

Biochar is a very powerful soil enhancer, which makes the soil more fertile, boosts food security, and reduces the need for some chemical fertilizers. Given all of biochar’s qualities it is capable of aiding farmers in meeting the demand of a growing population and reducing the need for more fertilization.

In addition to learning valuable information about biochar and its properties, our team also learned a variety of information about its production and various techniques to produce it. As it was found, biochar is commonly produced by backyard gardeners and soil enthusiasts alike. These enthusiasts and gardeners often produce biochar in small, batch-process cooks that result in high ash content and inefficient cooking.

Over the course of project learning, it was discovered that there are also some companies in Europe that are working to produce medium-scale, standalone biochar reactors. These reactors produce their own heat energy and biochar exclusively. These systems are designed for small business and production, they don't appear to be very versatile or able to be scaled up.

Concept Development[edit | edit source]

Early concept design for a biochar reactor began with research into the world of existing designs. Various models and prototypes are available in a variety of online publications. To find ideas, inspiration and known working designs, our team spent several weeks researching biochar reactors online. To further our understanding of our goal and mission, our team visited the University of Idaho Steam Plant and were given a tour of the plant's wood-fired boiler and feed-stock supply system.

During early design stages, our team researched and found information describing a variety of backyard reactors made from countless recycled objects. Of these designs, several in-ground "planted" reactors were found. These systems simply burned the input biomass as feed-stock in an ultra-low oxygen environment to produce small quantities of biochar underneath a layer of ash and charcoal. These systems were designed primarily for homeowners and gardeners who wished to produce a small amount of biochar.

Other small-scale designs found included a cone-shaped reactor that used heated airflow to prevent oxygen from entering a burn-container. This design, lovingly called "The Cone" by our team, allowed the biomass feed-stock to burn and smolder on top of a layer of biochar covered in ash. This system, too, used ash and low oxygen to produce biochar directly underneath an open flame. Although both systems were described as highly effective and extremely simple to build, neither provided any room for development to allow for continuous flow.

Later, after reviewing online descriptions of various biochar reactors, our team visited the University of Idaho Steam Plant and got an up-close look at what makes the boilers so effective. The tour gave our team a first-hand view of different methods of biomass transportation including augers, belts, and elevators. During the tour, and shortly afterwards, our team began brainstorming a variety of ideas using these various conveyors to create a continuous-flow biochar reactor. The tour also opened up a variety of questions about the method of heating the reactor.

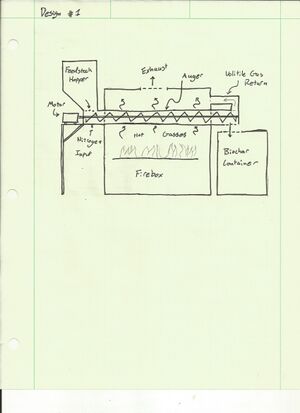

One of the very first models developed was that of the "Through-Boiler" design. Team members pitched the idea of placing a sealed auger-based conveyor directly through the heart of an existing boiler. This method would provide powerful, direct heating of the biomass, and it would allow for very short cook times. However, from this design, a variety of questions and problems were discussed. The first of many was how practical it might be to drill, or cut, holes in the sides of an existing boiler or firebox; not to mention how practical might it be to seal these new holes. Another question arose from the very method of fast cook-times. The amount of biochar in relation to volatile-gas and bio-oils is often related to the temperature of the cooking environment. Higher temperatures often mean less biochar, more gas and oil. Ultimately, this idea was set aside for more practical designs.

Following the first design, an external version of the "Through-Boiler" design was brainstormed. Known as the "Surface-Reactor" (not pictured), this design solved the problem of drilling holes in the sides of an existing firebox. This design also resolved the issue of extreme temperatures from direct heat from the fire. This solution, however, also spelled ruin for the design. After consulting Scott Smith, the University Steam Plant's resident expert, it was found that skin temperatures of the boiler are only approximately 450 degrees Fahrenheit. This temperature was lower than desired for production of biochar, rendering the design useless.

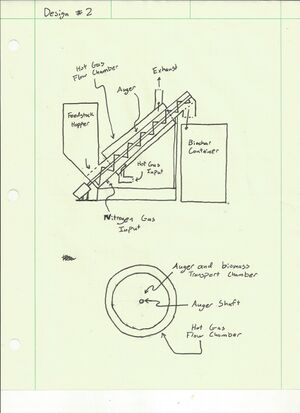

Following these designs, the first practical model was developed. The "Inclined Auger" system relied on exhaust gasses from an existing boiler or firebox to produce the necessary temperatures to cook biomasses into biochar. This method solved several problems with very few realized concerns. By using exhaust gas, the Inclined Auger would be able to control the temperature of the reactor by using an exhaust valve and a system of blowers. The system also required very little interference with the existing boiler or furnace. This proved to allow the reactor a more modular and transportable design, increasing value and ease of use. This system used an inner- and outer-shell design, transporting biomass through the inner chamber as it was cooked into the resulting components. The outer-shell conveyed the heated gasses, allowing them to directly heat the pipe that contained the biomass and driving auger.

This first practical model was widely accepted by team members as it showed great promise. Ultimately, however, the design was found large and cumbersome for prototype testing and development; with this, the inclined boiler saw great revision.

To allow for a more practical prototype development, our team decided to remove the inclined nature of the first practical design. Instead using a horizontal path of motion, our final design retained all of the valuable features from the Inclined Auger model with more practical functionality. With this new-found idea, our team was able to craft a system around existing and available parts including a large shop-cart serving as the base and a 55-gallon barrel that would act as the boiler, and a provider of heat for the reactor prototype.

In the course of one evening, our team was able to hash out the basic structure of the design and take a considerable number of concerns into account. This design proved to be very practical on paper as it allows our team a wide array of configuration methods. A variety of ways to incorporate parts whose placement was uncertain was gained by use of the horizontal design with the shop-cart.

Seeing the potential for this design, our team moved forward, creating 3-D renders of the prototype to further visualize the magnitude and impact of the machine.

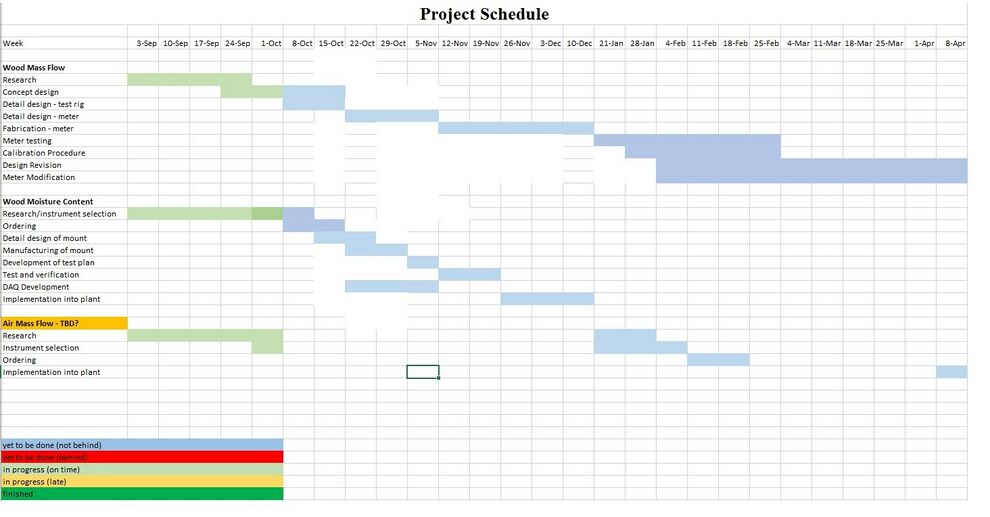

Project Timeline[edit | edit source]

Competitions, Demonstrations, and Awards[edit | edit source]

Our team has spent great effort in developing our concept and designing our prototype. We firmly believe that this design yields great potential beyond the academic environment as a full-scale system, and as such we have participated in several business and design pitch competitions. We have won some of the competitions we've entered and with the help of three University of Idaho College of Business students (Charles Dolar, Audrey Wootton-Franusich, and Devin Kohles) we were able to demonstrate our idea to business professionals from around the state.

University of Idaho Pitch Competition[edit | edit source]

Moscow

Our team competed in the University of Idaho's 2017 Idaho Pitch competition. Self proclaimed as a program that "gives innovators and entrepreneurs from across the university the opportunity to practice their presentation skills, build confidence, and learn how to work a reception - while presenting their ideas to a group of business and professional judges." Even with little business background or preparation time, our team was able to excel to the third-place position, winning $750.00 that we are using to further develop our design. Our success with Idaho Pitch ignited interest in our team from Idaho Entrepreneur Director and Instructor, George Tanner, who has encouraged and supported our team in continuing to promote our design in Boise and Spokane at competitions during the spring of 2018.

Boise Pitch Competition[edit | edit source]

Boise

Our team entered and was accepted for a pitch competition in Boise similar to that held by the University of Idaho. The competition took place on the 17th and 18th of March. Our team worked closely with three Business students to further develop a business model and other elements necessary for the competition. The experience was very valuable to the participating team members, and our team won $1,000 at the competition.

University of Idaho Engineering Expo 2018[edit | edit source]

Moscow

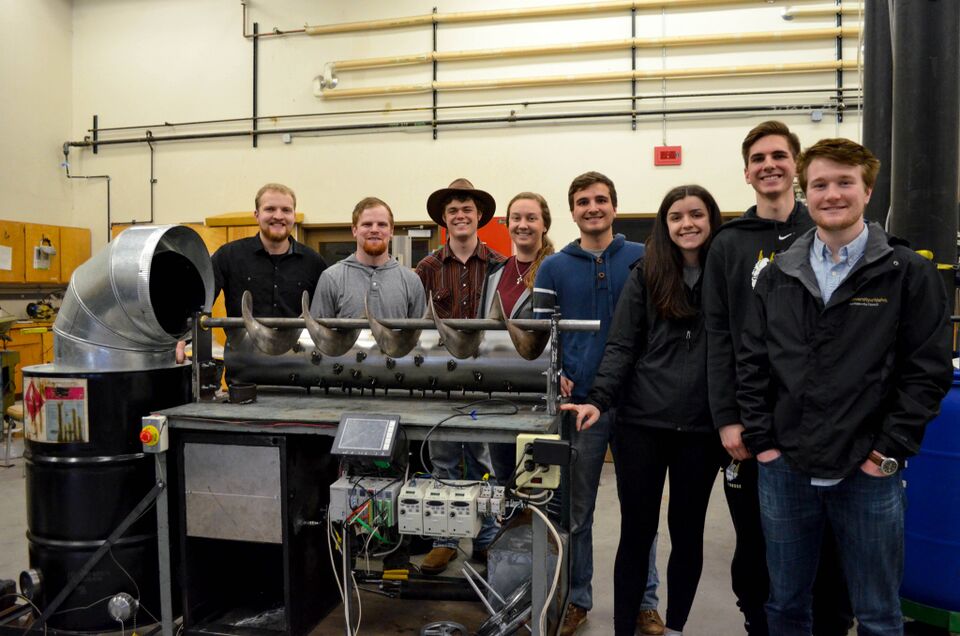

Our team will be demonstrating our completed prototype at the 2018 University of Idaho Engineering Expo. We have worked to ensure that our system can work in a "demo-mode" where we can demonstrate the moving parts without actually having to ignite the boiler. Thus we will be able to demonstrate the flow of our system without having to actually start it.

Test Results[edit | edit source]

Low-quality biochar can be just as harmful as its high-quality counterpart is helpful. A great many backyard gardeners and growers have learned how detrimental poor biochar can be to the soil and garden environment. Poor biochar can be acrid, thus adding unneeded acidity to the garden soil. Poor biochar also isn't very porous, and thus can't retain nutrients or water well.

Preliminary Biochar "Pipe" Quality Tests[edit | edit source]

As an initial benchmark our team decided that it would be valuable to run some initial tests on biochar production. With some assistance from graduate student Brian Hanson, our team was able to conduct tests on biochar of various materials at different temperatures. The results have helped to guide our team towards some of the thermal requirements before mentioned.

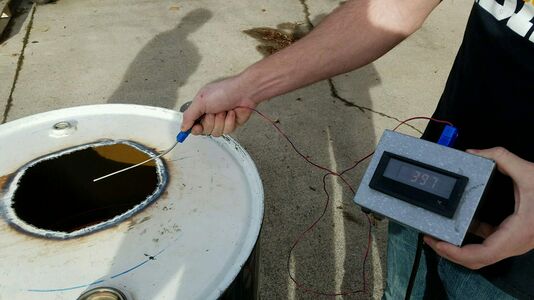

To complete our tests, our team used a testing apparatus consisting of a metal pipe caped and sealed at each end. The metal pipe provided a zero-oxygen environment since after being filled with biomass, the pipe was filled with the inert gas nitrogen and then sealed. This apparatus was then placed inside an oven and "cooked" at various temperatures for varying lengths of time. We cooked a variety of materials to see the differences between the resulting biochar material.

Our team cooked such materials as wood chips, coffee husks, and wood fiber. This was important to our development since although our project primarily deals with wood chips, the other materials could prove to be future biomass sources.

Biochar Reactor Quality Tests[edit | edit source]

Initial testing of the biochar reactor has proven to be successful after only a little testing and troubleshooting. Our first biochar cook test was conducted without the use of any nitrogen gas being introduced. This, of course, lead to some of our biomass combusting, but even with combustion, we were able to produce biochar successfully. This proved to be a eureka moment for our team as it gave promise for future developments.

Some system issues have prevented extensive testing of the ability to produce biochar on a continuous level, but ultimately, the system is successful in producing biochar. Perhaps the two largest issues that prevent these tests are the fact that the auger subsystem is susceptible to "locked" or "bound" operation where it will not rotate and that the pyrolysis chamber does not reach the desired temperature of 450°C falling short at around 350°C.

DFMEA Analysis[edit | edit source]

Through the process of developing our design, our team realized a variety of potential error conditions or problems that could result in either a system shutdown, or worse, a system failure.

From our compilation of error conditions in our DFMEA report, we realized that there are great concerns with several subsystems in our project. Two of these subsystems are directly related to the production process, they are the Auger Subsystem and the Boiler Subsystem. Additionally, a third category is the electrical and control system whose errors ultimately will stop operation of the system.

Auger Subsystem[edit | edit source]

The auger subsystem can see a great deal of failure conditions due to our method of design and fabrication. Noted in detail in the Future Work section, some of these issues may be resolved by either a finer process of fabrication with better methods and tools, a more robust design compensating for various issues, or a combination thereof.

Luckily, although there is potential for dangerous conditions due to combustion (and subsequent damage) in the system, most of the issues result in a much less dangerous condition. Often, merely shutting-down or stopping the system to clear a blockage, bound shaft, or over-tightened bushing will resolve the issue. Thus these problems, although still critical due to the fact that they prevent biochar production, are often not dangerous or life-threatening.

Boiler Subsystem[edit | edit source]

From analyzing the DFMEA report, it is clear that there are a great deal of potential error conditions that arise from the boiler's subsystem. Also notable from the report is that most, if not all, of these error conditions may lead to very concerning or dangerous situations. Several of these errors lead to an fire-hazard which could not only damage the system, but could lead to injury of those operating the system. These situations, however, are not unlike situations that could be experienced with a boiler of any size or magnitude.

Here too, however, there is good news. Although this prototype utilizes its own personal boiler, the full-scale model for this system will utilize a full-size, existing boiler. One whose performance and characteristics are well known and understood. This means that the biochar production system should not be so overly-concerned with the effect of these issues since although they may be pertinent to the prototype, they may not have great affect on the full-scale system.

Electrical and Control Subsystem[edit | edit source]

Perhaps the most apparent error condition appears in the electrical and control system. One feature intended for safety commonly halts the system (as it was found during operation), that feature is the Emergency-Stop (or E-Stop) buttons. These E-Stop buttons were found to be extremely easy to press, perhaps just a bit too easy. Although it is good to be able to stop the system easily, it is necessary to prevent false stops, and these buttons don't prevent false stops well. Often times, an operator would inadvertently activate the E-Stop without even knowing.

Other issues with the electrical and control system result in error conditions whose results (although critical) that may not be so dangerous as the other parts of the system. This leads us to understand that the electrical system may be a critical component, but may not result in damaging or dangerous conditions if an error condition arises.

Team Members[edit | edit source]

| Photo | Biography | Discipline |

|---|---|---|

| From Coeur d'Alene, Idaho; Jake Hall formed a passion for mechanical engineering growing up working in the automotive industry. Through various job endeavors, mechanical systems and problem solving have always been a fascination of his. This led to his pursuit in attaining an engineering degree at the University of Idaho. | ME | |

| From Boise, Idaho. Adam O'Keeffe was destined for attending the University of Idaho because his whole family has gone to the University of Idaho. His enjoyment of the outdoors and living an active lifestyle dictates his daily life. His fondness for problem solving lead him to the Biological Engineering field. | BE | |

| Rachel was raised on her family's ranch in Jamestown, California where she developed a passion for the outdoors. She chose to attend the University of Idaho and major in Biological & Agricultural Engineering where she could apply an interest in math and science to solving agricultural and environmental problems. | BE | |

| Born in Moscow, Idaho, Will Seegmiller was raised in Troy, Idaho and developed a great interest in Mechanical Engineering. He aimed to solve practical problems that have a potential to advance technology and improve the human condition. | ME | |

| From Weippe, Idaho; Joe Stanley grew up around 4-H youth programs. He worked on a variety of electrical projects that he applied to these youth programs, and his fascination with electrical engineering was formed. | EE | |

Project Construction Photos[edit | edit source]

Future Work[edit | edit source]

Although our design and prototype were successful and we were able to create a functional system, a variety of elements could, and perhaps should, be improved on future designs.

Project Recommendations[edit | edit source]

Through the process of building and designing our project, our team found a variety of ways that our project could be improved. For future development, we have included our recommendations for improvement here.

Notes for Improvement[edit | edit source]

Due to the restrictions on our project, we fabricated most of our system with a variety of parts from numerous varied sources, the result of this was a system whose operation has the potential to be very sporadic and could be unpredictable. Fabricating a reactor with high quality parts, tools, and practices would greatly mitigate the system's rate of problems.

Although our ability to produce biochar is continuous, our ability to collect it is not. Our current prototype and design only allows us to collect the amount of biochar that fills the collection bin for our system. When this bin is filled, the process must be stopped while the bin is emptied. In a full-scale or larger-scale prototype, it may be possible to mitigate this problem by using some form of cooling system that prevents biochar combustion and a loading system that can be used to load the finished biochar into a bin, truck, or other container.

During our testing, we came across a few minor issues in the pyrolysis chamber that could lead to better operation if they were addressed. The first issue that we noticed is that we have too much clearance between the auger and the inner shell. This leads to the potential of binding the auger on a piece of biomass during normal operation. This issue should be addressed by reducing the clearance of the auger to shell. Increasing the size of the output from the pyrolysis chamber and the size of the input hopper would also help the overall operation of our system.

To ensure proper pyrolysis, future developments should increase the gear reduction ratio so that the auger rotates more slowly and we can effectively control the residence time of the system. Improving the pulley tension and reducing unneeded friction in the drive system would also make the system more efficient overall.

For testing purposes, adding a viewing port to the biochar collection chamber and increasing the size of the collection chamber bin should be considered. In addition, the sensors and equipment are quite reliable, yet not extremely accurate. Increasing their accuracy can significantly improve our ability to produce biochar reliably.

Another design feature that could easily be included into future prototypes and developments would be the inclusion of a third Emergency-Stop button located very near the auger's drive line and pulley system along with a cage for the pulleys and belts. This could prevent serious injury to operators and also increase safety and ability to shut down the system when an error condition arises near the area that has so many moving parts.

Features that Weren't Included[edit | edit source]

Our team decided early in the design process that making one system that combined electricity production, heat production, and biochar production would be extremely cumbersome and too much for the scope of our project. As a result, our team decided to cut back on our goals. Understanding that a variety of combined heat-and-energy production systems are available on the market, we made continuous biochar production our priority.

Making biochar production our priority lead us to create a continuous-flow system that used its own boiler. In the scope of a full-scale system, it should be necessary to incorporate this continuous flow system into either an existing boiler system or a specific system that incorporates all three missions; heat, power, and biochar. Thus, a feature to be added for future systems would be a the ability to incorporate a biochar reactor into a full-scale boiler system.

Sensing and measuring levels of Oxygen in our system is crucial, however, due to our team's budget and understanding of processes, we were unable to use practices for effective oxygen measuring. Our system can only determine oxygen levels on a binary level; either high oxygen or low oxygen, no middle ground. Future designs could incorporate high-temperature rated oxygen measuring devices that can register oxygen as a measurable value that a process engineer could use for advanced control schemes.

Summary

- Make a larger hole for the biochar exit hole from the reactor to the biochar bin.

- Make a greater gear reduction so that the residence time may be extended.

- Make the auger tolerance much tighter.

- Add a viewing port to the biochar collection bin.

- Move the boiler thermocouple to a location where it isn't susceptible to as much variance.

- Make the input hopper larger, more accessible, and in a truly vertical orientation.

- Make the collection bin easier to remove.

- Make fine control of the large fan more accurate.

- Improve fabrication methods.

- Perfect thermocouple accuracy.

- Improve oxygen sensor.

- Improve pulley tension and reduce friction for belts.

- Add E-Stop button near pulleys and belts

- Cage pulleys and belts to prevent injury

Estimated Scope of Next Steps[edit | edit source]

Our design team took two semesters to design and build a biochar reactor with an initial budget of $2,000 which was later increased due to winnings from the Idaho Pitch Competition and Boise Pitch Competition. This, however, is only the initial prototype for our system. To make the system viable, effective, and productive, the prototype would need to be expanded, improved, and perhaps even enlarged.

Enlarging the system is perhaps the most likely route, and it would require an enlarged budget due to the fact that a great many parts for our design were second-hand or waste parts from previous projects. For our project, we were able to acquire spare parts from the University Surplus, previous projects and the remaining necessities were purchased for our design. Enlarging our budget must accommodate purchasing all of the required parts (including those that were free or those that our team didn't need to purchase for the prototype) and the necessary expansion and enlargement of the main system components. This sort of expansion could leave the cost of production as low as $3,000, or it could leave the cost much higher, in the neighborhood of $15,000.

The next steps for this design also include investigating the viability of possible operation methods and the ability and likelihood of taking the project full-scale as a business enterprise. If it were to be deemed possible and recommendable, decisions of operation methods should include the following:

- One Central Location: The biochar reactor is located in one place and biomass input is delivered to its location while biochar output is delivered to the various locations where it is consumed. All shipping costs and resulting profits are the responsibility of the biochar company.

- Multiple Locations, Business Partnership: Multiple biochar reactors are built and distributed to regional locations where they can be used in conjunction with existing boilers at said locations. Each reactor and the resulting biochar is owned by a central biochar company, said company shares profits with the partnering companies who own and operate the boilers.

- Multiple Locations, Device Sale Only: Multiple biochar reactors are built and distributed to regional locations where they can be used in conjunction with existing boilers at said locations. Each reactor and the resulting biochar is the property of the the company who owns the boiler and has purchased the biochar reactor outright.

As these are only possible options, they only name a few from a great list of possibilities. Further business planning would be required if this plan is to continue to a full-scale market.

Project Development | 2019[edit | edit source]

This project is currently undergoing some new development and working through a secondary prototyping stage. For more information and up-to-date documentation, please review the new Mindworks page: Beta Version

Related Project Work[edit | edit source]

Other University of Idaho Capstone Groups have conducted research and development in the fields related to Biochar. Here are a list of such projects with links to their pages.

Additional Team Documents[edit | edit source]

Project Records

Meeting Minutes

| September | October | November | December | January | February | March | April |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Presentations

- Design Review

- Snapshot 1

- Snapshot 2

- Snapshot 3

- Engineering Expo Technical Presentation

- Business Executive Summary

Full Document Archive